The Way Things Work

This week we got introduced to the basics of open making and hacking everyday objects. Guillem and Victor are a fantastic duo. They embody the ideals of sharing and open-source movement. Working with them was an inspiring and rewarding experience that clearly showed us the value of tinkering with everyday objects in a curious, playful and immersive way.

Know thy gadget

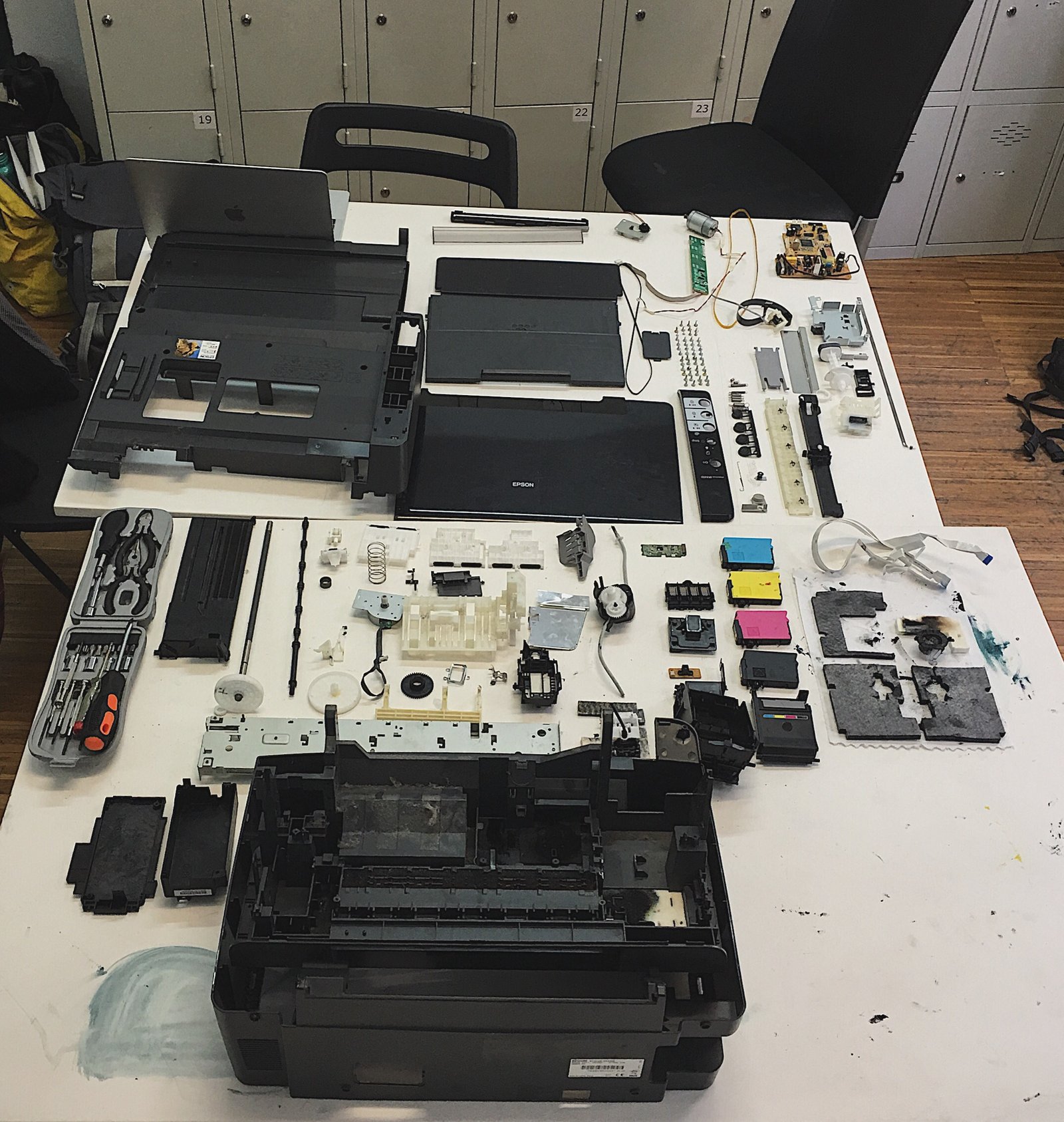

The major theme throughout the week revolved around how things work (surprisingly). An exercise of disassembling retired printers, phones, electric kettles and coffee makers was a useful way to get a glimpse of the intricacy and engineering might embedded in seemingly simple everyday objects. It also served as a powerful reminder of the wastefulness of a lifestyle based on relentless consumption, planned obsolescence and ever-shorter product life cycles.

The course has made us look at objects as interfaces – a majority of consumer products are means to satisfy specific psychological, social and physiological needs and desires. Therefore, if we put aside those common outcomes, we can subvert those interfaces and hack everyday objects to experiment with different potential uses for a given thing (or parts of it). Such as using a stepper motor from an old printer to make a small wind turbine to charge a phone.1

When our devices stop working we are accustomed to take them to an ‘authorized’ repair shop or throw them away and buy new ones. Other times, the device is completely functional, but we just feel the desire to own the latest versions.

Wet My Leaf

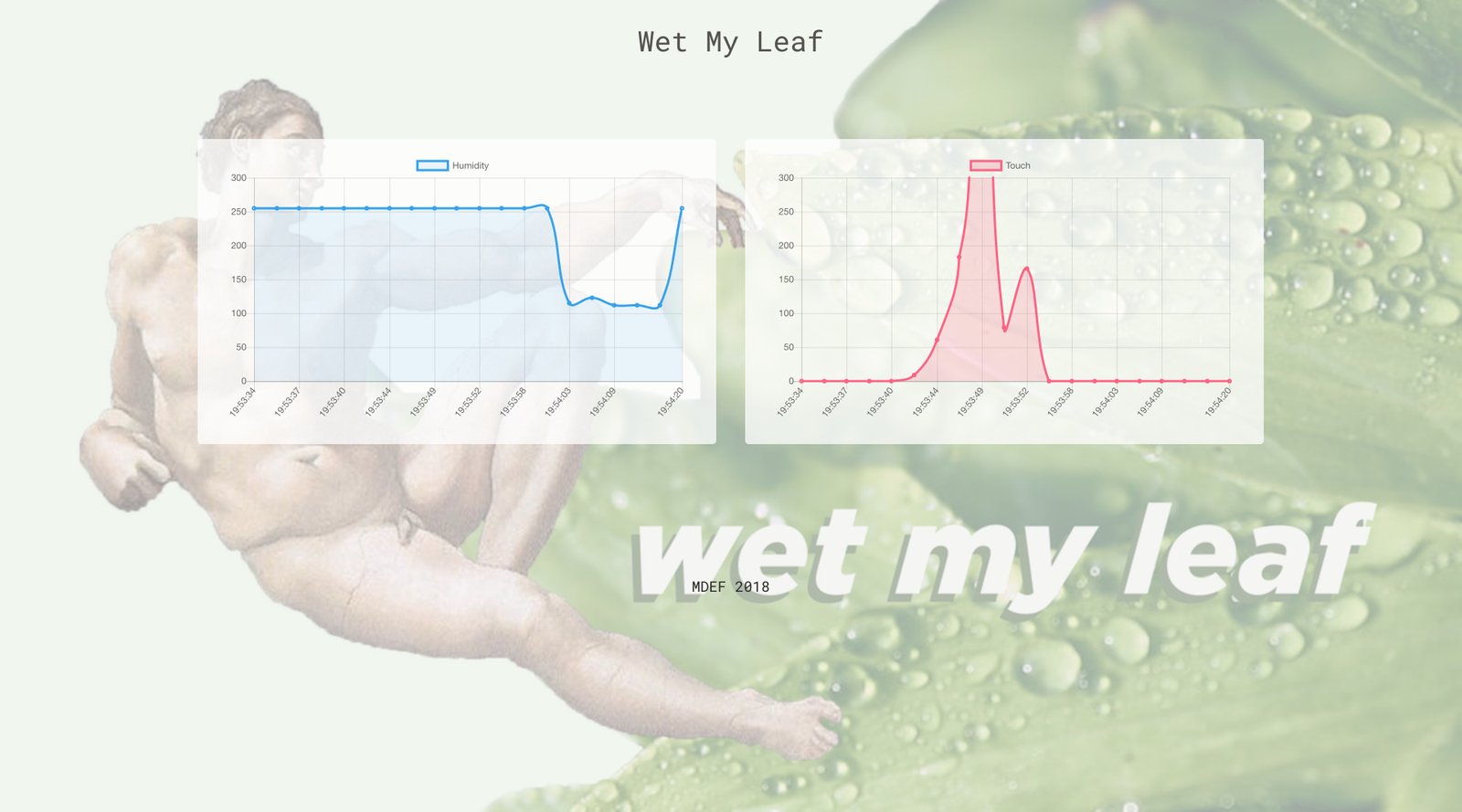

Our group started off with an idea of working with plants which culminated in aptly named ‘Wet My Leaf’ project. The title came about as a result of an idea to monitor humidity of a plant’s soil and let the plant notify you that it needs watering. We have toyed around with different outputs, such as turning on different LEDs based on the humidity or more obnoxious ones like emitting annoying sounds when a plant needs watering. In addition to humidity sensor, we have also attached a capacitor to the plant to detect touch.

At the end of the week, all the groups in the class connected their hacked-together devices to a local Node-RED server that allowed us to create various input/output flows using an accessible and user-friendly interface. This was a true aha moment – it showed us how easy it is to connect different machines to create modular and extensible sensors network. A particularly enjoyable configuration used a touch input from a plant as a trigger for a blowing horn.

A neat byproduct from our group project was an online dashboard for real-time monitoring of humidity and capacitor sensors attached to a plant. It was built using GatsbyJS, Firebase, Chart.js and is hosted on GitHub pages.

Takeaways

Coming from a software development background, I found the concept of sketching in hardware liberating. It encouraged us to deconstruct ordinary objects and repurpose their salient components in a novel and playful manner. Our experiment with attaching sensors to a plant was relevant in relation to my final project. I find the idea of embedding intelligence and extended sensing capabilities at the level of material especially interesting.

Overall, the course has shown us the value of hacking and tinkering with everyday objects. Maybe more importantly, it illustrated how open-source knowledge sharing lowers the barrier for entry and creates a potential to awaken a maker side that is dormant in all of us since early childhood.

“When wireless is perfectly applied the whole earth will be converted into a huge brain, which in fact it is, all things being particles of a real and rhythmic whole. We shall be able to communicate with one another instantly, irrespective of distance. Not only this, but through television and telephony we shall see and hear one another as perfectly as though we were face to face, despite intervening distances of thousands of miles; and the instruments through which we shall be able to do his will be amazingly simple compared with our present telephone. A man will be able to carry one in his vest pocket.”

— Nikola Tesla, interview (1926) 2